What is a Linguist?

According to Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, the first meaning of the word ‘linguist’ is the following: “a person accomplished in languages, especially: one who speaks several languages.” I would definitely say that this definition fits me perfectly. As some of you might know, I am a multilingual scholar with robust control of several modern languages. I currently speak Italian, French (Parisian), American English, and Latin American Spanish. Not only am I fluent in all of these languages, but I have honed my skills as a professional translator through extensive training in French and English Translation at the University of Turin, Italy, in 2008 and 2010 (500 hours!), and I have been working as a freelance translator since 2015. Below is the list of the languages I currently master, with a short description of how I got to such a significant level of proficiency. I hope that I will be able to add more languages soon –– I do have some basic knowledge of German and Modern Greek, but I am still very far from fluency! Sigh!

Italian is my mother tongue, as I was proudly born in Pavia, in Northern Italy. I have a thorough knowledge of Italian since I have studied the History of the Italian Language (E. Soletti, Turin), Italian Literature (C. Leri, Turin, and C. Allasia, Turin), and Italian Dialectology (T. Telmon, Turin). Although Italian is the official language of Italy, it is not widely known that the country boasts more than thirty spoken dialects. Indeed, standard Italian evolved from the decision by the newly-unified Kingdom of Italy to use the Tuscan ‘dialect’ (spoken mainly by the upper class of Florentine society) as a model for the official state language in the late 19th century. The majority of the other dialects spoken in Italy evolved from Vulgar Latin (like Sicilian, Neapolitan, Sardinian, etc.), whereas the other minority languages belong to other Indo-European branches, more specifically Germanic, Albanian, Slavic, and Hellenic. I am fluent in two dialects: Piedmontese (North-Western Italy) and Calabrian (Southern Italy).

French is my Heritage language. My mother is a native French speaker, so she would only speak to me in French throughout my childhood, which helped me naturally assimilate the language. To take full advantage of my near-native proficiency in French, I studied at an Italian-based international high school (Liceo Classico “General Govone,” Alba, Italy) in which certain subjects (such as Geography, History, French Language, and Literature) were taught exclusively in French by French teachers, with annual visits to Côte d’Azur. Continuing my love for France and the French language, I moved to Paris in 2011, where I lived until 2016. Not only did I pursue my graduate studies in France, but I even wrote my Ph.D. dissertation entirely in French!

Part of my mother’s family was living in the U.S. (Florida and Ohio) when I was a child, which sparked my interest in learning the language at the age of seven. As a teenager, I listened to my favorite Californian bands and became acquainted with American English by translating their lyrics. In 2014, I completed the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) with an excellent score, given my stay at UCLA as a Visiting Researcher. As a current resident of Los Angeles, I use English most of the time in my everyday life.

In my early twenties, I spent two years at a Spanish Catholic boarding school for young women in Paris (Foyer de la Jeune Fille – Hogar de la Joven, Congregación de María Inmaculada). Most nuns came from Spain or Latin America, meaning I needed to learn Spanish to communicate with them or suffer in silence. My Mexican and Colombian friends here in LA have helped me dramatically reach a quasi-native proficiency in Standard Latin American Spanish. I have also learned a lot of dialect intricacies by being a massive fan of telenovelas and reggaetón music! The dialects I am most familiar with are Mexican Spanish and Colombian Spanish.

What is a Historical Linguist?

The second meaning of the word ‘linguist’ according to Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, is: “a person who specializes in linguistics.” Again, this is correct. I am specialized in linguistics, i.e., in the study of human language. There are different kinds of linguistics according to the aspect of human speech they focus on. There are computational linguists, forensic linguists, psycholinguists… In my case, I am a historical linguist. Historical linguistics is the scientific study of how languages change over time by reconstructing their earlier stages and understanding their kinship relationships. Of course, I cannot “speak” ancient languages. Still, as a historical linguist, I have philological and linguistic competencies in some of them (and familiarity with the history, art, and culture of the civilizations that used them). While writing my Ph.D. dissertation, I specialized in another sub-discipline, i.e., historical sociolinguistics, the study of the relationship between language and society in its historical dimension. This approach is beneficial when intra-linguistic data alone cannot account for developments that require searching for extra-linguistic causes of change.

As I have already mentioned, Ancient Greek (and Greek civilization) is my specialty, as I have studied this language since I was fourteen. Throughout my B.A., my M.A., and my Ph.D. I have learned about: Mycenaean Greek (C. De Lamberterie, Sorbonne); Ancient Greek Dialects (M. Egetmeyer, Sorbonne); Homeric Greek (B. Vine, UCLA); Classical Greek, Language, and Literature (A. Aloni, Turin, and D. Arnould, Sorbonne); Koine Greek, Language and Literature (A. Billault, Sorbonne, and E. Berardi, Turin); Medieval Greek, Language and Literature (A. M. Taragna, Turin); Greek Epigraphy (F. Lefèvre, Sorbonne); Greek Papyrology (J. Gascou, Sorbonne); Greek Paleography (R. M. Piccione, Turin); Greek Historiography (S. Cataldi, Turin); Greek Archaeology and History of Greek Art (F. Gualdoni, Brera).

My research pursuits have focused on language contact phenomena involving Ancient Greek and other languages since my undergraduate studies. In this respect, my research work has been inherently coherent throughout the years as I have explored this topic from different synchronic and diachronic angles.

My first original research in connection with language contact involving Greek was my Bachelor’s thesis, entitled La versione gotica di Neemia V, 13–18; VI, 14–19; VII, 1–3 [The Gothic Version of Nehemiah 5.13–18; 6.14–19; 7.1–3], in which I analyzed from a linguistic point of view the three short passages remaining of Ulfilas’ translation of the Old Testament from Greek into the Gothic language. Through etymological and morphosyntactic analysis, I showed how Ulfilas’ Gothic could be considered a dynamic language in its need to preserve its original Indo-European and Germanic traits and, conversely, to innovate through the adoption of different linguistic structures influenced by Latin and Greek. My thesis was defended in July 2011 at the University of Turin and obtained the maximum score in the Italian University system, i.e., 110 summa cum laude.

The second ancient language that I learned in high school is Latin. Latin is the most important language of the Italic family, a branch of Indo-European whose earliest known members were spoken on the Italian Peninsula in the first millennium BCE. Throughout my B.A., my M.A., and my Ph.D. I have studied: Old Latin (M. Fruyt, Sorbonne); Classical Latin, Language and Literature (G. Garbarino, Turin, G. F. Gianotti, Turin, and M. Ducos, Sorbonne); Medieval Latin, Language and Literature (A. Vitale Brovarone, Turin); Latin Epigraphy, (S. Giorcelli, Turin); Latin Historiography (S. Giorcelli, Turin, and G. Traina, Sorbonne), and Roman Archaeology and History of Roman Art (F. Gualdoni, Brera). Besides Latin, the known ancient Italic languages are Faliscan (the closest to Latin), Osco-Umbrian, and South Picene (M. Fruyt, Sorbonne, and B. Vine, UCLA).

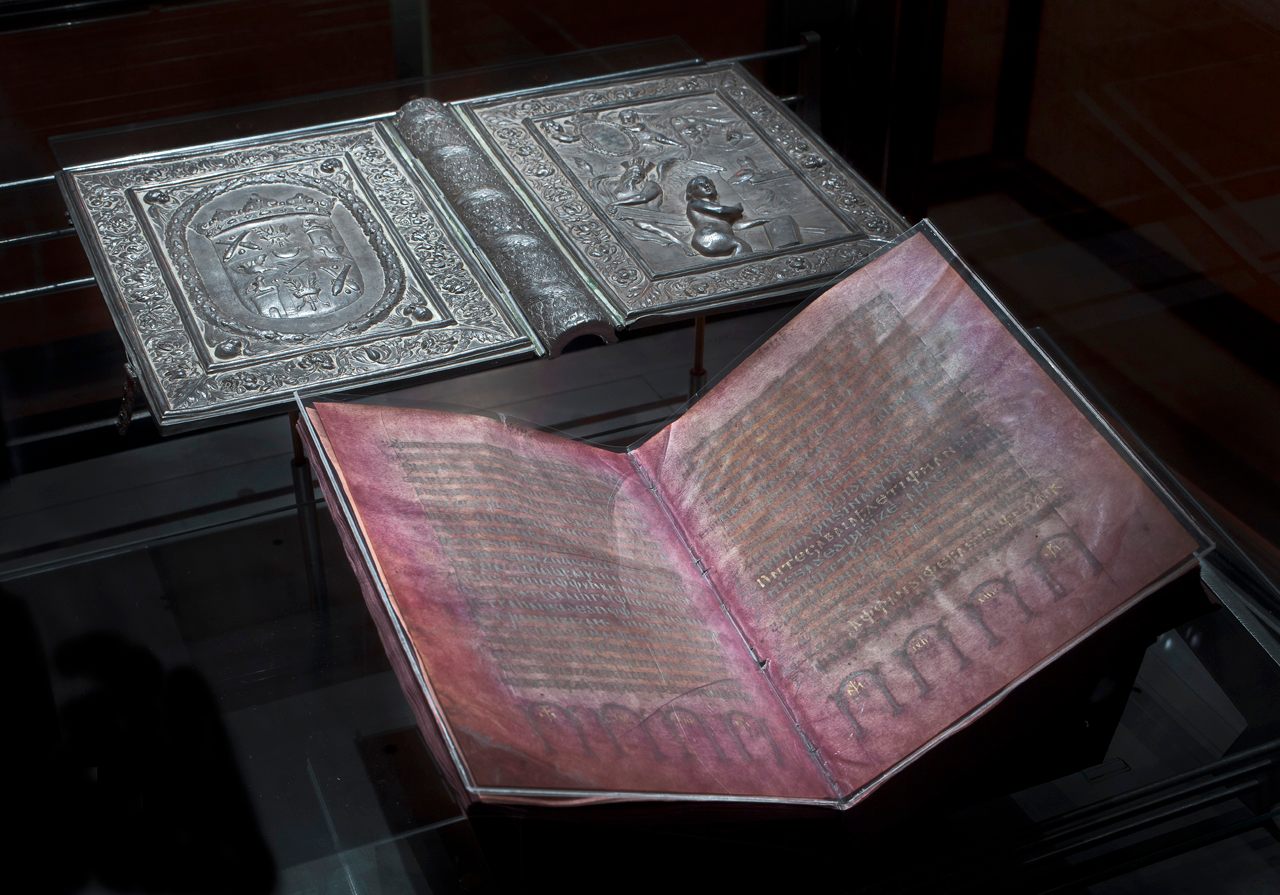

Concerning Gothic, it is the earliest Germanic language attested in any sizable texts, but it is extinct, i.e., it lacks any modern descendants. The oldest document in Gothic is Ulfila’s translation of the Greek Bible, which dates back to the 4th century CE, and was crafted in the Balkans. I studied this language at the University of Turin under the supervision of V. Corazza Dolcetti. With her, I have also learned another Germanic language, Old Norse. By this name, we call a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlements. It chronologically coincides with the Viking Age, the Christianization of Scandinavia, and the consolidation of Scandinavian kingdoms from about the 7th to the 15th centuries CE.

Then, in my Master’s thesis entitled “Pappù, pému mía ffágula!” Analisi e commento di cinque favole esopiche in lingua grecocalabra [“Pappù, pému mía ffágula!” Analysis and commentary of five Aesopic Tales in Calabrian Greek], defended at the University of Turin in 2013, I analyzed five Aesopic tales in a Greek dialect spoken in Calabria. In this Southern Italian region, I spent my childhood. First, I isolated some morphological, syntactic, and lexical phenomena typical of this dialect because of the prolonged contact with Romance dialectal varieties while elaborating a new method of transcription of Calabrian Greek. Finally, I identified the Greek elements deriving from the Medieval stage of Greek and the ones probably deriving from a previous one, directly related to the Southern Italy Ancient Greek Koiné period. My Master’s thesis was awarded the maximum score possible, 110 summa cum laude.

At the beginning of my Ph.D. at Sorbonne University, I got interested in the relationships between Ancient Greek and a fragmentary language spoken in Anatolia, Phrygian. Numerous grammatical and lexical isoglosses show that Ancient Greek and Phrygian are genetically connected, having shared common prehistory in the Balkans (so-called “Balkan-Indo-European”) before the Phrygian populations started their migratory flows to Central Anatolia around the 12th century BCE. After many centuries of independent development, as evidenced by the Paleo-Phrygian corpus written in the Phrygian epichoric alphabet (9/8th–4th centuries BCE), the Macedonian invasion of Anatolia (334–333 BCE) intensified the interactions between Greek and Phrygian to the extent that Phrygians abandoned their epichoric alphabet and started using the Greek one to write in Phrygian (4th century BCE). In the Roman Era, after many centuries of “silence,” a new set of inscriptions exhibits the final attested phase of the language, known as Neo-Phrygian (1st–3rd centuries CE).

Greeks and Phrygians underwent profoundly different historical developments, which eventually led the Greeks to progressively identify the Phrygians as the incarnation of the stereotype of the barbarian slave in the 5th century BCE, even if, paradoxically, their idiom was the closest one to Greek among all the other Indo-European languages. The complex relationship between Greeks and Phrygians had never been studied from a sociolinguistic point of view, although it seemed a very productive field of investigation. This was the starting point for my doctoral dissertation entitled Problèmes linguiquistiques du rapport entre Grec(s) et Phrygien(s) [Linguistic Problems of the Relationship between Greek(s) and Phrygian(s)], which was eventually defended at Sorbonne University in June 2019 with highest honors.

My semantic exploration of the ethnonym ‘Phrygians,’ as well as my sociolinguistic and pragmatic analyses of significant literary passages (in particular, Timotheus of Miletus’ The Persians 140–161) and epigraphic evidence (more specifically, the bilingual Greek/Neo-Phrygian funerary curses), has produced a more nuanced understanding of the reciprocal perception of Greek and Phrygian identities, indirectly from the Phrygian inscriptions, directly from the Greek literary texts. Beyond all the stereotypes of the Phrygians as barbarians and slaves, products of the Hellenocentric traditional view that emerge from the Greek literary texts, the “revival” of the Phrygian language in the Neo-Phrygian inscriptions in the Roman Era seems to me to provide evidence of the survival of linguistic and cultural Phrygian identity through the centuries in Anatolia. This can be interpreted as a striking manifestation of the preservation of diversity in the culturally and linguistically Hellenized world that followed Alexander’s conquest (334–333 BCE).

Learning about Phrygian, a Balkan language spoken in Anatolia naturally led me to study the Anatolian languages stricto sensu with the support of M. Egetmeyer (Sorbonne) and C. Melchert (UCLA). The best-known Anatolian language is Hittite, considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language, and it is preserved in cuneiform inscriptions written between the 17th and the 13th centuries BCE. By the Late Bronze Age, Hittite had started losing ground to its close relative Luwian. The two varieties of Luwian are known after the scripts in which they were written: Cuneiform Luwian and Hieroglyphic Luwian. The latter survived until Assyria conquered the Neo-Hittite kingdoms in the 8th century BCE. Alphabetic inscriptions in the Anatolian languages derived from Luwian (i.e., Lycian, Milyan, Carian, Sidetic, Pisidian) and in Lydian (a unique and problematic Anatolian language) are fragmentarily attested until the early first millennium BCE, eventually succumbing to the Hellenization of Anatolia in the 4th century BCE.

In conclusion, I report a passage of an interview of mine with Thomas Wasden (you can read the integral version here): “Many people ask me: ‘Why putting so much effort into languages or stages of language that are actually dead and are not useful anymore in everyday practice? You cannot go to Turkey and speak Hittite…’ Honestly, I do it because it is fascinating. Again, there are two sides, inseparable, like the right and left brain, like the need for hard-core science and the humanities in our society. On the one hand, there is the scientific challenge, that adrenaline-inducing thrill of discovering something new, getting further than your predecessors. Finding a new etymology for that word, maybe the right and definitive one this time, the one that will bear your name, decoding that ancient inscription, or even better, cracking an entire undeciphered writing system. And then, on the other hand, there is what I call poetry. Discovering that, somehow, despite space and time, we are still the same. We still laugh and cry for the same things. We love and hurt in the same way. Nothing scared Egyptian pharaohs more than oblivion. Studying ancient languages and penetrating ancient texts gives voice to the dead civilizations, thus redeeming them from oblivion.”