Interview With Thomas Wasden: Historical Linguistics And The Humanities

Why Do You Put So Much Effort Into The Study Of Dead Languages?

Today I will share with you the edited version of an interview of mine that my friend Thomas Wasden (Graduate Student in Neuroscience at Brigham Young University, Provo, UT) posted on his personal LinkedIn page on January 7th, 2021. The interview is about my interest in historical linguistics and, in general, about the future of the humanities. Enjoy!

Thomas: What got you interested in linguistics? Historical linguistics? Hellenic studies?

Milena: I have been interested in linguistics since childhood, as I was born in a multilingual family. I used to speak French with my mother, Italian with my father, and a Southern Italian dialect (Calabrian) with my grandmother. I have always been fascinated with human language and that the same item could be called differently according to the language used. As a, I started noticing intuitively the differences and the similarities between the different languages I used to speak. When I was told that Latin was the basis for French and Italian, my interest in historical linguistics was officially born. Concerning my specific passion for ancient Greek, it started when I learned that the weirdest words in my grandmother’s dialect were actually Greek. Calabria was part of Magna Graecia and subsequently occupied, among others, by the Byzantine Empire. Although endangered, there is still a Greek-speaking community in the region. I have always loved ancient Greek more than any other language. At least to me, ancient Greek is THE language. When I started studying it at 14 years old, it was the most challenging thing I have ever done. I remember that I preferred Latin at first because it was easier. But then it got me bored. In Greek, there are so many possibilities that I always find something new and exciting.

T.: What other disciplines does your work interface with?

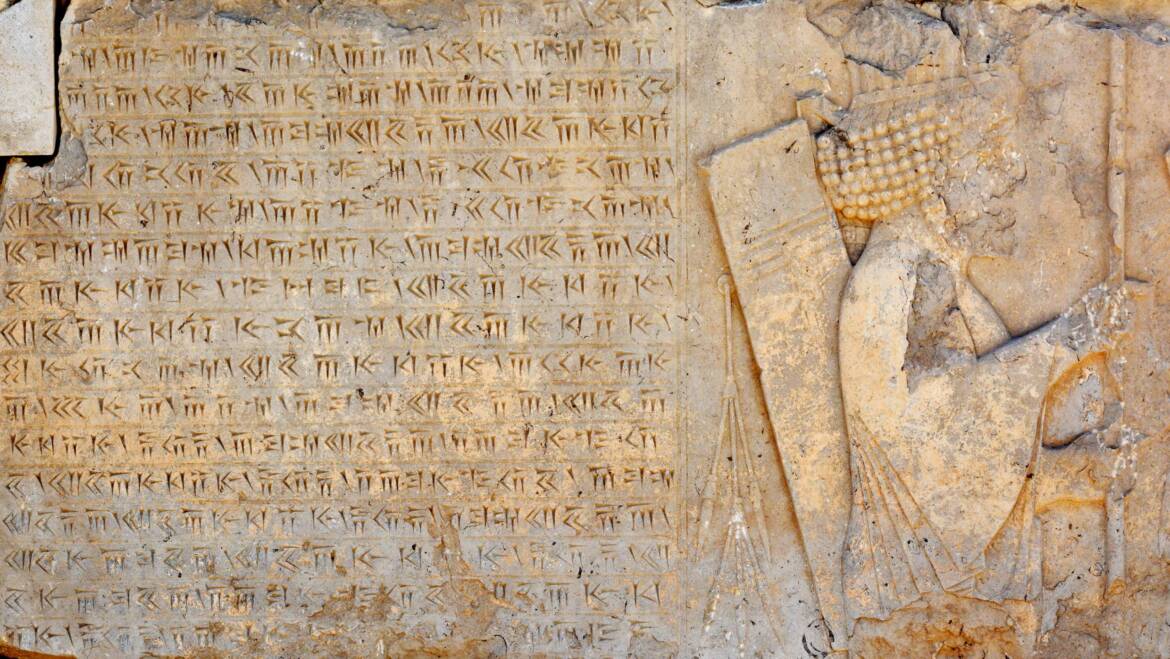

M.: My work interfaces mostly with ancient history since it is essential to put language into the historical context in which it was spoken, and with archeology, as in many cases, ancient inscriptions can be on monuments, statues, pottery, etc.

T.: What does it take to become an expert in your field?

M. It takes years, and years, and years of study to become an expert in historical linguistics. Even now, I do not think I got anywhere close to knowing everything I would like to know. First, you need strong proficiency in the ancient languages that interest you (and possibly a decent familiarity with the history of the populations that spoke them). Ancient languages are objectively very hard. They have entirely different structures compared to today’s languages — above all English — and require a lot of practice to be mastered. Then, you need a genuine concern for the diachronic aspects of language, a fair deal of linguistic intuition, and good judgment. If you notice that you lack any of those items (or are unwilling to acquire them), then historical linguistics is not the right field for you. But consider it carefully: you might be the next treasure hunter who will have the opportunity to uncover answers to crucial questions! Then, it depends significantly on your main area of interest. Since I have a precise focus on Ancient Anatolia, I had to study ancient Greek and many other languages spoken in that area to produce new content. First, we have languages of the 2nd millenary BCE, such as Hittite and Luvian. They are super complicated because they were written in Cuneiform and Hieroglyphs. Then, we have the languages spoken in the 1st millennium BCE. These, even though they are written in variations of the Greek alphabet, are even more complicated because they are fragmentarily attested and, in most cases, not even entirely decipherable. So, well, I am working on becoming an expert, too.

T.: What advice would you give an aspiring historical linguist?

M.: Do they exist? Aspiring historical linguists?! I’m just kidding… I would give the following advice to an aspiring historical linguist: I know ancient languages are complicated, and I know academia is competitive and challenging, but don’t give up! If you have decided to commit to such a niche field, try to find your own space by specializing in something your colleagues are not doing yet. Take advantage of your own learning experience by improving a bit every day while exploring with curiosity and without prejudice all the aspects of the ancient languages that interest you the most. New ideas for research will come out, and they will be great! At least, that’s what I did…

T.: What do you enjoy doing for your job the most?

M.: The thing I enjoy most doing for my job is discovering new things! Nothing thrills me more than getting further than my predecessors while studying a specific phenomenon. I am fortunate to be affiliated with Harvard University since I can access most of the books and resources I need directly online. If something is not yet digitalized, I can ask for it to be scanned and sent to me by email. This is a dream come true because I can finally avoid libraries and work from home! As a student, unfortunately, I didn’t have access to all the digital material we have now. It was ten years ago, and things changed fast in the last decade. I have never really enjoyed studying in the university library since I get easily distracted by other people and cannot concentrate properly. So, I remember consuming the photocopier toner at the University of Turin more than once to be able to consult the books at home. Also, giving talks about my research in progress is really cool. When you reach my level, you get invited to conferences as a featured speaker, making you feel like a rockstar! I am currently writing a monograph on the exotic linguistic portrayal of the characters in Timotheus of Miletus’ “the Persians,” a lyric poem written at the end of the 5th century BCE. It is an understudied and underrated poetic composition found on a papyrus at Abusir in 1902. I love Timotheus’ linguistic creativity expressed through neologisms and compounding and his sensitivity to the musical possibilities of the words.

T.: The humanities are to a certain degree on the decline (at least in my opinion), and the study of the classics even more so. Why do you think that is? What do the humanities offer? Why should people study them more?

M.: Yes, you are right. Unfortunately, the humanities are on the decline, and the study of the classics even more so. I think that these are areas of knowledge perceived as “useless” in our postmodern world, or in any case, less valuable than hard core sciences, computer sciences, or economics, for example. Like art or music, you cannot make easy money out of them, and exceptional talents in such fields are pretty rare. I assume that one reason for the unpopularity of the humanities is the lack of security that they imply. However, as we have a right brain and a left brain with different functions, we need both scientific/technical knowledge and humanistic/artistic knowledge in our society to guarantee its correct functioning. Would you deliberately mutilate your brain? I do not assume so. In the same way, we cannot mutilate our society. Plus, we all appreciate beauty. Is beauty necessary? Of course not. But still, we all need it.

T.: What would you say to a student who wants to study the humanities, but doesn’t feel they provide a stable enough income?

M.: To a student who wants to study the humanities, but does not feel they provide a stable enough income, I would say to be honest with themselves, and try to figure out what they really like in order to be happy. Nothing is worse than feeling frustrated because of a job that does not fulfill your deepest ambitions and passions. As in every field, grants for the best students and helps of any sort do exist. Trying to pursue excellence is always fundamental. Compared to other majors, students who choose to study the humanities, the classics, etc., are really interested or even passionate about these disciplines, and because of that, they are usually pretty good students. Then, it is true that when you study humanities your career path will not be as defined as your friend’s who studied pharmacy or nursing studies, for example. Your career will not be as linear A –> B –> C, but it will certainly have a more articulated path. As I always say, developing certain “transferable skills” it is what matters the most in your academic career. Maybe you won’t talk about Shakespeare’s Macbeth every day, but you’ll have an articulate vocabulary and a writing good enough to open the doors for exploring a good number of career possibilities that value those skills. For example, there is a big demand for writers — wait, I am not talking about ‘authors’, i.e. writers who get published by real publishers and become famous thanks to their literary accomplishments — I am simply talking about people who have a good command of English grammar and punctuation rules. They are pretty rare outside of the Humanities! It is possible to easily reach six-figure income through a copywriting career, for example.

T.: In conclusion, how would you sum up the importance of your field to someone with no background or interest in historical linguistics?

M.: Many people ask me: “Why put so much effort into languages or stages of language that are actually dead and are not useful anymore in everyday practice? You cannot really go to Turkey and speak Hittite….” Honestly, I do it because it is fascinating. Again, there are two sides, indivisible, like the right and left brain, like the need for both hard-core science and the humanities in our society. On the one hand, there is the scientific challenge, that adrenaline-inducing thrill of discovering something new, getting further than your predecessors. Finding a new etymology for that word, maybe the right and definitive one this time, the one that will bear your name, or decoding that ancient inscription, or even better, cracking an entire undeciphered writing system. And then, on the other hand, there is what I call poetry. Discovering that, somehow, despite space and time, we are still the same. We still laugh and cry for the exact same things. We love and hurt in the same way. Nothing scared Egyptian pharaohs more than oblivion. Studying ancient languages and penetrating ancient texts gives voice to the dead civilizations, thus redeeming them from oblivion.

.

Add Comment